About

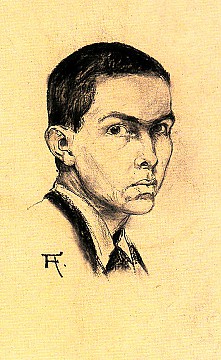

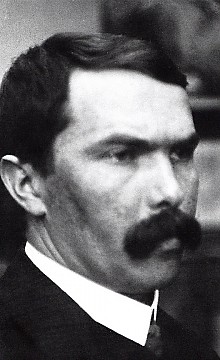

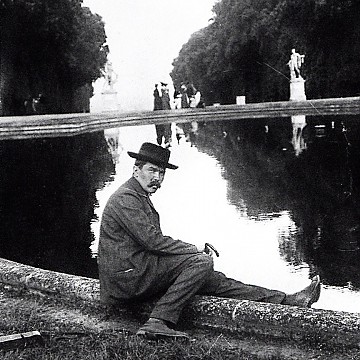

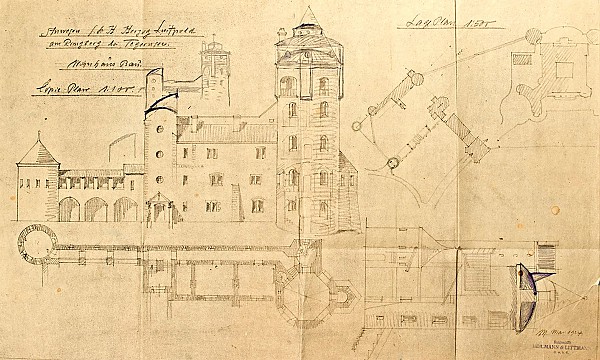

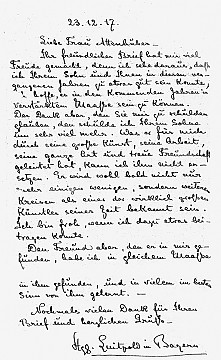

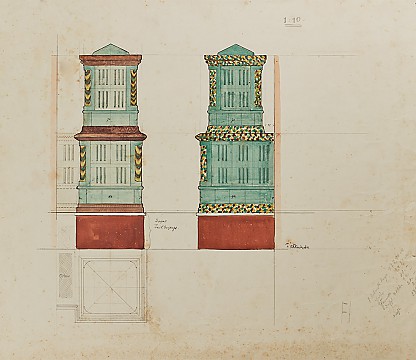

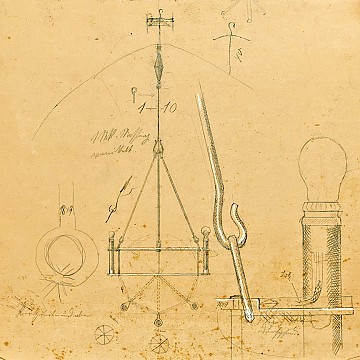

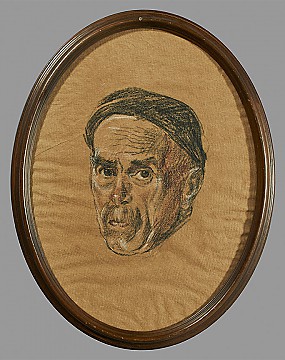

Everything that makes Schloss Ringberg a total work of art bears the hallmark of one man: Friedrich Attenhuber. As a painter, architect, interior architect and the designer of all the furnishings, tiled stoves, lamps, wall decorations and even the smallest details, he created a unique overall ensemble over a period of 35 years on behalf of Duke Luitpold of Bavaria.

Who was this generalist, the last »house artist« of the Wittelsbachs?

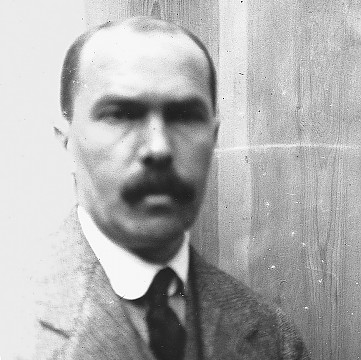

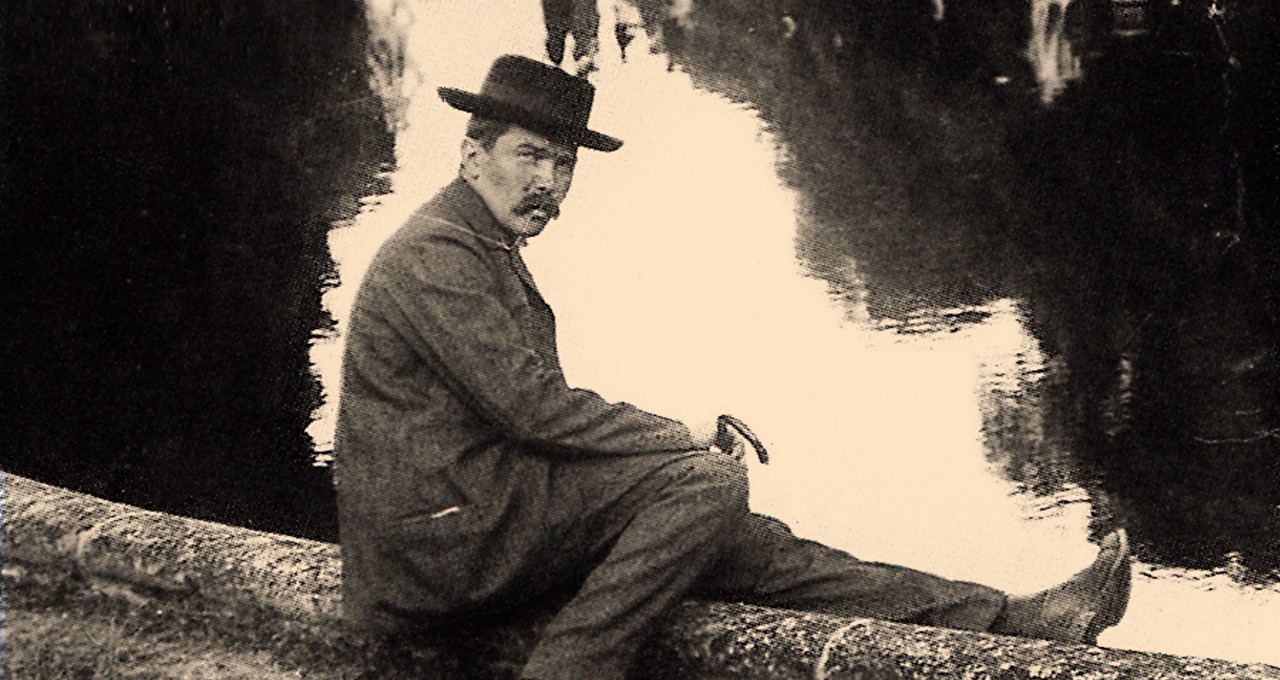

Attenhuber was born on 19 February 1877, the son of an unmarried factory worker, Sofie Rahn, in the Upper Bavarian ducal city of Burghausen. He obtained his surname as a result of his mother's subsequent marriage to Johann Attenhuber, who adopted him and his younger brother in 1882. Friedrich grew up in a working-class district of Munich on Schießstättstraße in the Schwanthaler Höhe district. Very little is known about his childhood or adolescence.

VIDEO

About

-

Artistic career

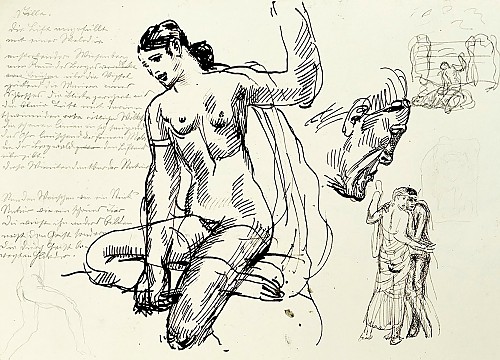

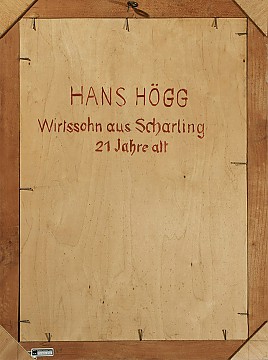

In 1898, the 21-year-old took up a course of study in painting at the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, which he presumably paid for with lithographic commissions. His stylistic orientation was inspired by the tradition of South German Impressionism, to which the artist group known as »Die Scholle« was devoted.

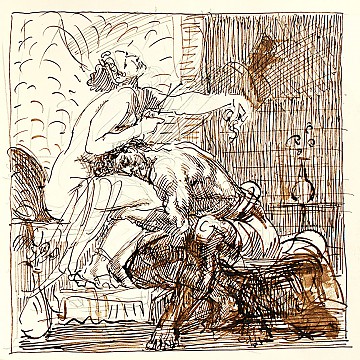

His teacher Ludwig von Herterich, who belonged to the first generation of the Secession, a progressive artistic movement at the end of the 19th century, had a major influence on him. The movement was founded in Berlin, Munich and Vienna by young artists who were disillusioned with the academy system. Herterich put his pupil Attenhuber in touch with the famous Max Liebermann, President of the Berlin Secession, at the end of his studies. The famous artist wrote to the 27-year-old Attenhuber: »With reference to [...] we courteously request your works »Halbakt«, »Verhöhnung Christi» and »Aktstudie« [...] to display at our exhibition.« At the Berlin exhibition of 1904, which exclusively featured members of the Munich Secession, Attenhuber was represented with two paintings. He appeared to have a distinguished career ahead of him.

-

Turning point

However, his destiny took a different course in 1910 as a result of contact between Ludwig von Herterich and the young Duke Luitpold in Bavaria after he recommended his 30-year-old protégé as an art teacher.

The teacher-pupil relationship quickly developed into a friendship. The Duke made Attenhuber his personal travel companion in the period from 1910-1912. They mainly travelled around the Mediterranean region. While travelling, they came up with the idea of working together on the construction of Schloss Ringberg. The Duke assigned overall responsibility to Attenhuber.

-

From painter to generalist

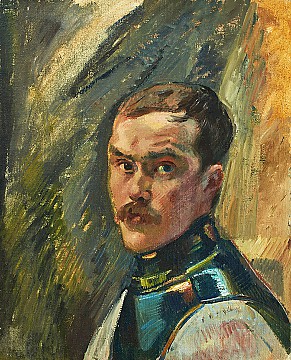

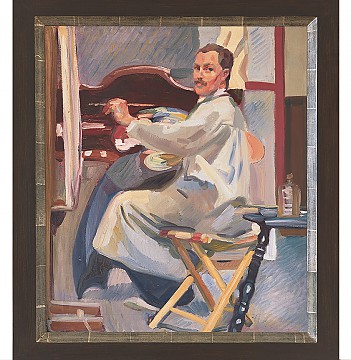

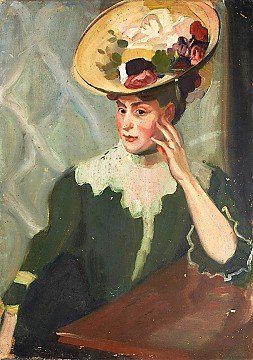

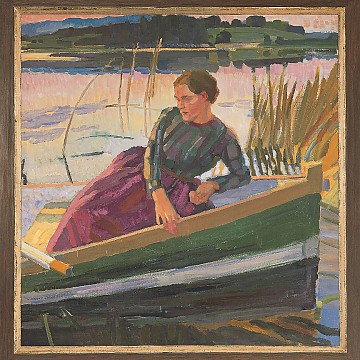

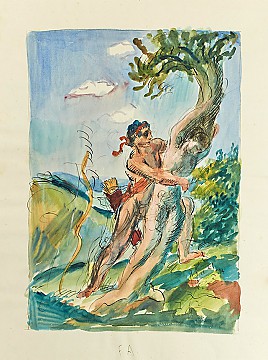

In his early work, Attenhuber painted a number of highly proficient portraits and landscapes in Expressionist style. They can be seen today on the second floor of the castle. The paintings testify to his great talent.

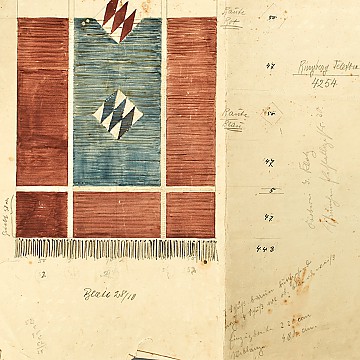

However, increasing demands were placed on the painter over the following years. Until Attenhuber was conscripted in 1917, he was responsible for the entire external and internal development of the castle, designed furniture, tiled stoves, lamps, tapestries, carpets and living accessories.

At the end of the War in 1918, he looked forward to resuming his painting career, but the poor economic climate and lack of commissions led Attenhuber to return to Ringberg. Here he produced countless plans for the never-ending design of the castle. Ringberg was and remained an enormous building site where nobody was able to live. The Duke, however, wanted to move into his castle as soon as possible after the devastating War. Attenhuber was blamed for every delay in construction. The Duke accused him of working too slowly and of being unable to keep up with the frequently changing requirements and ideas. The relationship between the developer and artist increasingly deteriorated. To cope with the mounting pressure, Attenhuber employed artisans and tradesmen from the Tegernsee Valley, thereby gaining an insight into ceramics production and carpentry. Ultimately, however, he was to remain an autodidact, which is evident, for example, in the more or less unsuccessful proportions and combinations of the furnishings. Attenhuber was a visual artist who saw everything from the perspective of painting and drawing, and therefore designed rooms as though he was applying colour strokes to his canvas.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, the Duke rarely visited Ringberg; the Tegernsee had become a popular destination with leading figures in the Nazi regime. Attenhuber would also have preferred to have left this environment. But financial considerations and his strong attachment to »his« castle prevented him from a change of course.

-

Downfall

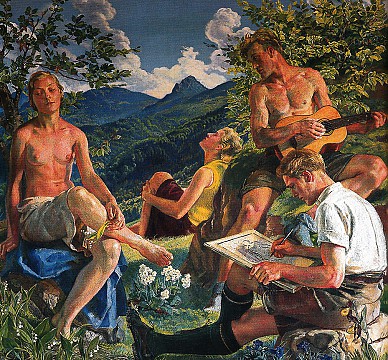

Attenhuber subsisted at a minimum existence level. He was provided with all the painting equipment he required, but lacked contact with the art world. He had neither models nor the freedom to visit art exhibitions. Art journals were a substitute for actual contact. Attenhuber's style changed radically and finally evolved into Nationalist Realism, which is associated with the art of the Third Reich. It can only be speculated as to why Attenhuber changed his style of painting in the 1930s. There is absolutely no evidence of Attenhuber having a political affinity with Nazi ideology.

The Duke only visited the castle to give Attenhuber further instructions or to have his portrait painted by him. The relationship between the two key figures was shattered.

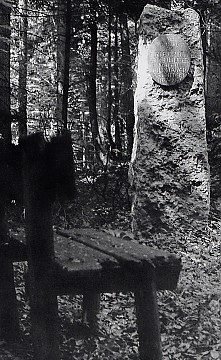

Attenhuber responded to his changed role by withdrawing into himself. The situation came to a head in the early 1940s and ended in the suicide of the once promising painter in 1947.

After his death, Duke Luitpold continued his castle project. As he lacked expertise in the statics and proportions of the building, he engaged the architect Heinz Schilling. The interior of the new building remained a shell construction. It can be presumed that the Duke recognised at the end of his life that he had treated Attenhuber unjustly.

GALLERY

GALLERY

VIDEO

Biography

-

1877–1907

1877

Attenhuber is born on 19 February in Burghausen a.d. Salzach as the son of the unmarried weaver's daughter Sofie Rahn.

1898

He takes up his studies at the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in Munich.

1904

His talent attracts attention: Attenhuber is invited to join the Berlin Secession.

1907

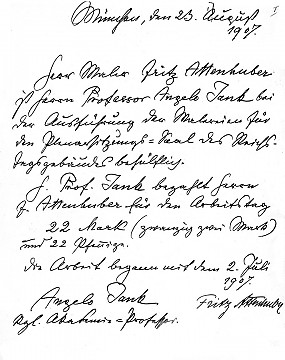

A contract to work on the paintings at the Reichstag building in Berlin follows.

-

1907–1912

1907/8

Attenhuber, the protégé of the academy lecturer Ludwig von Herterich, appears for the first time in the Munich address book as a painter and is recommended to Duke Luitpold in Bavaria as an art teacher.

1910

Attenhuber accompanies the Duke, thirteen years his junior, on many trips through Europe, Asia Minor and the African Mediterranean region.

1911/12

He works outside of his main field of expertise as a painter for the first time and produces the design drawings for the Duke's »Florentine villa«.

-

1915–1918

1915/16

All of the furniture, lamps, wall design, tiled stove and fireplace in the Study is produced according to his designs.

1917

Towards the end of the First World War he is still deployed as a military engineer with a surveying unit, primarily in North Africa. He and Luitpold regularly exchange letters of friendship until his involvement in the War.

1918

On 27 November, he returns from the War with 50 Marks of severance pay and 15 Marks of conduct money - not enough to allow him to resume his former career as a painter. He makes contact with his friend the Duke and produces further drawings for the castle's entire furnishings. He also takes over the position of architect, site manager and head of production. The painter becomes a ducal generalist.

-

1920–1947

1920

The friendship between the artist and Duke is overshadowed by growing disagreements during the coming years. The interiors of most of the staterooms and living spaces are completed over the following years.

1930

He gives up his studio in Munich. Attenhuber moves to Schloss Ringberg becoming financially and socially dependent upon the Duke. The social and artistic isolation increasingly stifles his creativity and leaves him lacking inspiration and the strength to face life.

1942

The ducal administration informs Attenhuber that he will not receive a financial settlement in the event of the sale of the castle.

1947

Attenhuber plunges to his death from the castle Tower on 7 December.